There’s an often spoken claim in regards to cinema that “they don’t make them like they used to”. Ella McCay (a frustrating title to spell with lead actress Emma Mackey’s name in the back of the mind), the first film from James L. Brooks in 15 years, takes that to heart. Right off the bat, we’re introduced to an original character living a noble and successful life in an esteemed occupation, promotion on the way, married to her high school sweetheart, smothered by her family, and narrated in-person by an acclaimed character actress. Also included are: breezy flashbacks to fill in the details, an “uh-oh” scandal at its center, and a wide range of supporting players, all excited to just be in a project directed by a legend. If that wasn’t enough, the score by Hans Zimmer’s effervescent score seems revived from an entirely different, more hopeful era.

As the James L. Brooks filmography (and the cringe-inducing Simpsons marketing) would leave you to believe, it’s meant to just be a “relax and have a good laugh and a good cry time with the family”. Brooks’ early work defined the magic of the Reagan-era dramedy, where a perfect cast with great chemistry could come together, have a visibly good time, and recite snap-crackle-pop dialogue. It’s true that studios have sadly moved on from that theatrically-released “light-touch”, all-star movie-making that genuinely pleases everyone and used to be monoculture. Most of that style repurposed into 8 episode Netflix series and other algorithmically-curated streaming content sludge. Ella McCay seeks to bring that old-school essence back and bellyflops like a dying fish.

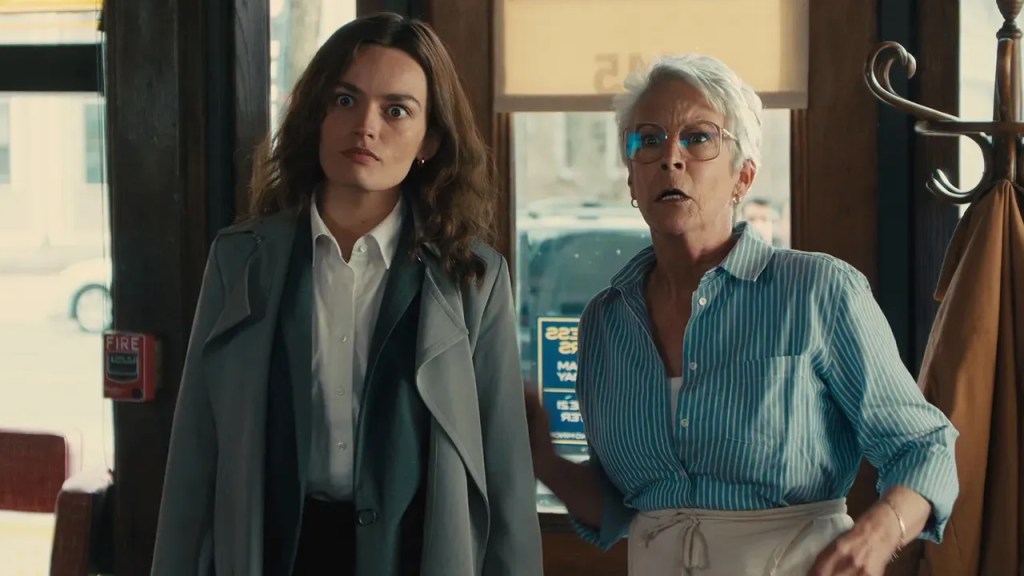

At age 16, Ella McCay and her brother Casey are confronted with their father Eddie’s infidelity (Woody Harrelson, in a very Harrelson role) and later on, their mother Claire’s passing (Rebecca Hall, fully wasted). Her Aunt Helen (Jamie Lee Curtis, very possibly directing her own performance) has been the supportive constant in her life, being a surrogate parent for Ella in her last year of high school and owning a restaurant that is conveniently side-by-side to her house. Ella grows up to be Lt. Governor for this unnamed state, under current Governor Bill Moore (Albert Brooks, making all of this look easy) who has announced he is vacating his position to seek a cabinet position under a certain president who is unnamed, but given the year is 2008, we can guess. This allows Ella to step in and take her predecessor’s place.

There’s only one problem: she and her husband Ryan (Jack Lowden, unmistakably British and struggling to enunciate through a East-Coast dialect) are under the threat of an unseen reporter who may break a story of the two consummating their love in a government building. All the while, Eddie has been making attempts to get back into his children’s lives and her brother Casey (Spike Fearn, a fascinating actor who must think he’s in a different movie), now struggling with possible agoraphobia and anxiety disorder, yearning to reclaim the heart of Susan (Ayo Edebiri, blessed with just one scene), “the one that got away”. Oh, but wait- there’s more! We also devote time to Ella’s security detail Trooper Nash (Kumail Nanjiani, just happy to he here), who for a lengthy bit is paired with a second hand partner (played by Brooks’ son Joey Brooks). Julie Kavner squeezes into all of this playing Ella’s elderly secretary Estelle, who is there both to narrate and to crack a few soft one-liners. It’s a lot, and Brooks is no stranger to having large scope stories (and in Ella McCay’s defense- it’s under two hours!) so there is a world in which this was fine-tuned enough to click into place. But there are two enormous problems with the film. One being… its entire construction.

The structure is maddening. There are lengthy flashbacks to fill in details, sometimes unnecessarily so, zipping back and forth in a dizzying manner, forcing the same actors to wear hideous wigs with digital touch-ups. These are meant to establish dynamics and relationships, but characters will often change their entire personalities in one scene. Every big dialogue moment, and there are a lot, will begin with a conflict, get comedically manic, become abruptly serious, and then attempt to land on a level of poignancy. One or two of these would have done the trick, but Brooks seems to think every scene needs this. We beg you, they don’t.

The second problem is the cast. It’s not that anyone here is a bad actor, but there are only a few key roles that feel suited to these performers whereas everyone else is trying to make it work with what they’ve got. There is just a generation that is either long gone or aged out that syncs with Brooks’ rat-a-tat speech and optimism, the Holly Hunters or the Jeff Danielses or the Debra Wingers, who were born to speak that language, which was spawned off from the Howard Hawks era of performing style. 80s/90s Brooks or Harrelson would have fit the Jack Lowden role. 80s/90s Kavner would have fit the Curtis role. There is a version of this made 30 years with the ideal cast that just doesn’t exist today.

Ella McCay, a live-action Lisa Simpson all grown-up, is a role perfect for a young Holly Hunter and Emma Mackey is not the type of actress that evokes Hunter’s sensibilities at all. In fact, a bit the opposite. Despite that, Mackey gives everything she’s got to it and sporadically charms, but also feels (as most do in this cast) completely lost, where Ella’s mindset in a scene is not fully locked down before the camera rolls and is had to be improvised by Mackey on the spot.

It brings no pleasure to tear a movie down that is trying to do what many movies have stopped bothering to. Ella McCay strives to be optimistic feel-good cinema, but the results on the screen are a NyQuil fever dream. A Groundlings session per scene that can’t ever remember the point of its own narrative or what the characters are meant to be doing.

I haven’t even mentioned the “sex scarf” once and its mere existence begs its own questions that the world may not have time for.

Leave a reply to The Minnesota Movie Digest: Issue No. 170 – Minnesota Film Critics Association Cancel reply